Lichens in the Dolomites Are at Risk

As a consequence of climate change, some species will only be able to survive at the highest elevations, while many others – surprisingly – will shift downslope in search of areas with greater precipitation

Climate change is threatening the survival of lichens in the Dolomites and the Eastern Italian Alps. According to a new study led by researchers at the University of Bologna and published in Diversity and Distributions, around 40% of the species currently found in the area will only persist at the highest elevations. At the same time, many other species are expected – surprisingly – to move downslope, following areas with higher rainfall.

“Climate change will substantially affect the distribution of lichens in the Dolomites,” confirms Luana Francesconi, research fellow at the Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences at the University of Bologna and first author of the study. “Our analysis reveals an extremely heterogeneous response across species, and upward shifts – traditionally considered the dominant trend in mountain ecosystems – are less common than expected.”

Mountain ecosystems, considered among the most fragile and vulnerable on the planet, are undergoing profound transformations due to the climate crisis. The Alps are a striking example: in recent decades, the region has warmed at twice the rate of the average for the Northern Hemisphere, with direct consequences for the distribution of both fauna and flora.

In this context, lichens play a crucial role as sentinels for understanding the environmental impact of climate change. These organisms contribute to nutrient cycles, soil formation and stabilisation, and provide microhabitats essential for the survival of various species.

At the same time, their physiology makes them extremely sensitive to climatic factors. Lichens cannot actively regulate their internal water content and therefore remain in constant balance with external environmental conditions. As a result, changes in temperature and humidity expected over the coming decades could significantly affect their metabolic processes and growth capacity.

“Despite their ecological importance, lichens remain understudied organisms, and adequate data to assess how climate change affects their distribution have long been lacking,” explains Juri Nascimbene, professor at the Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences at the University of Bologna and coordinator of the study. “This is why we set out to help fill this gap by collecting and integrating high-quality data on the presence of lichens in the Dolomites and the Eastern Italian Alps.”

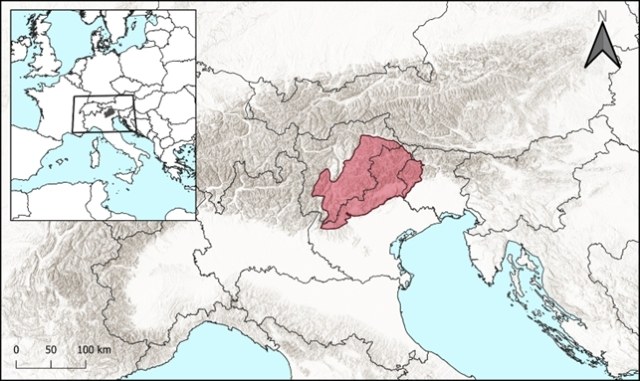

The project, coordinated by the University of Bologna, is called Dolichens. The dataset collected enabled researchers to develop a series of scenarios to understand how climate change will influence the distribution of lichen species in the Dolomites, identify potential “refuge areas,” and estimate possible upslope or downslope shifts.

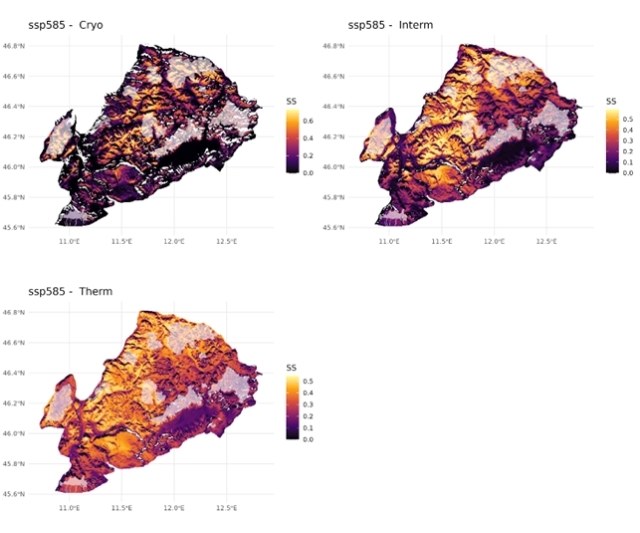

The research team used a dataset of 21,884 georeferenced occurrences to develop species distribution models for 272 lichen species. Using different climate scenarios – a mitigation scenario with significant emission reductions, and one reflecting the continuation of current trends – they were able to explore how distinct climatic trajectories may influence species persistence and potential distributional shifts.

“In general, lichen populations will tend to contract, finding refuge only in areas with more stable climatic conditions, such as the central Alps, characterised by a relatively stable continental climate,” explains Francesconi. “However, many of the areas identified as potential climatic refuges lie outside existing protected areas, which complicates conservation efforts—especially given additional pressures such as forest management and air pollution."

The results show that around 40% of the species will experience a reduction in the areas where they can survive: they will persist only at higher elevations and, in some cases, expand even further upslope.

Contrary to expectations, however, the remaining 60% of lichen species will not follow this upward shift. Some will instead move downslope, likely responding to changes in areas with increased precipitation, even at mid-elevations or on specific mountain faces. The Alps also host several “micro-refugia,” such as humid valleys or snowbeds where snow persists for many months, potentially ensuring the survival of different lichen populations.

“These results confirm the need to expand our knowledge of lichen diversity, distribution and behaviour: they are sensitive organisms, but ecologically essential,” concludes Nascimbene. “It will now be crucial to integrate these new scientific findings into conservation strategies, in order to safeguard lichen biodiversity in a context of rapid global change.”

The study was published in Diversity and Distributions with the title “Range Shift and Climatic Refugia for Alpine Lichens Under Climate Change”. The authors from the University of Bologna are Luana Francesconi, Michele Di Musciano, Luca Di Nuzzo, Gabriele Gheza, Chiara Pistocchi and Juri Nascimbene.