Giovanni Domenico Cassini and the birth of the world’s longest sundial, in Bologna

Portrait of Giovanni Domenico Cassini by Léopold Durangel. Cassini taught at the University of Bologna from 1650 to 1669

From the left nave of the Basilica of San Petronio, Giovanni Domenico Cassini looks up towards the back wall and traces, in the half-light, an imaginary line running diagonally across the floor, barely touching the bases of the massive columns. He knows it will not be easy, but what he has before him is a unique opportunity. If his calculations are correct, he may succeed in building an extraordinary instrument: a sundial of unprecedented size, able to observe the movements of the Sun with extraordinary precision. And to seek answers to questions that are still best left unspoken.

“Cassini had a very different temperament from Galileo: throughout his life he never made explicit statements about the hypotheses of heliocentrism and the Copernican system. He was very cautious, and above all interested in obtaining the means and instruments to pursue his research.” These are the words of Bruno Marano, Professor Emeritus of Astronomy and Astrophysics at the University of Bologna and President of the Committee for the Cassinian Year 2025: the programme of events celebrating the 400th anniversary of the birth of one of the greatest astronomers of all time.

The University of Bologna is among the promoters of the celebrations. Cassini lived in Bologna for many years, teaching at the University and making groundbreaking discoveries about the celestial bodies of the Solar System. And in Bologna, inside the Basilica of San Petronio, he also left what is still the world’s longest sundial. An extraordinary work, officially created to confirm the accuracy of the Gregorian calendar, but with which Cassini hoped to carry out other observations, not so easy to justify in the Papal States of 1655.

The Basilica of San Petronio, in Bologna: inside stands the world’s longest sundial, designed by Giovanni Domenico Cassini

“Cassini was born in 1625 in Perinaldo, in the Republic of Genoa, and studied mathematics and astronomy at the Jesuit College of Genoa,” explains Elisabetta Rossi, research fellow at the Department of Physics and Astronomy ‘Augusto Righi’ and at the University Museum System, who devoted her dissertation to Giovanni Domenico Cassini. “He arrived in Bologna in 1649, invited by Marquis Cornelio Malvasia to conduct observations at the observatory of his private villa in Panzano, in the province of Modena."

But Marquis Malvasia, besides being a passionate lover of astronomy, was also an influential member of the Bologna Senate, which at the time oversaw the University And in those years, the chair of mathematics and astronomy happened to be vacant.

“That chair had belonged to the great mathematician Bonaventura Cavalieri, who died in 1647,” explains Bruno Marano. “So Malvasia persuaded the Senate to hire the young Cassini, who however had to wait until 1650 to take up the post, because at that time one could not access the Archiginnasio Library, where the University was based, before the age of 25.” Elisabetta Rossi, research fellow at the Department of Physics and Astronomy ‘Augusto Righi’ and at the University Museum System, and Bruno Marano, Professor Emeritus of Astronomy and Astrophysics at the University of Bologna and President of the Committee for the Cassinian Year 2025

Elisabetta Rossi, research fellow at the Department of Physics and Astronomy ‘Augusto Righi’ and at the University Museum System, and Bruno Marano, Professor Emeritus of Astronomy and Astrophysics at the University of Bologna and President of the Committee for the Cassinian Year 2025

Despite his young age, Cassini quickly established himself in Bologna’s academic and scientific circles, so much so that just a few years later he was entrusted with the project of building a new sundial inside the Basilica of San Petronio.

“There was already a sixteenth-century sundial in San Petronio, of moderate size, built by Egnazio Danti: but the wall through which the sunbeam entered to bring it to life had been demolished in the early 1600s during works to expand the Basilica,” says Bruno Marano. “At that point, Cassini insisted on building a much larger one: he never declared it openly, but his idea was to create an instrument for making highly precise scientific measurements, far beyond what was required for liturgical uses or calendar checks.”

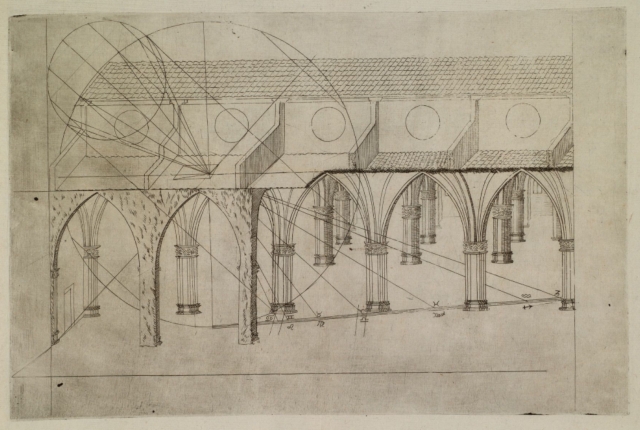

The project was grand in scale. The gnomonic hole—through which the sunbeam would enter—was to be placed some 27 metres high, creating a sundial that would span the entire length of the basilica, crossing it diagonally for nearly 67 metres. But such an ambitious design was also very costly, and Cassini needed a convincing justification to obtain the necessary funds from the Bologna Senate.

Drawing of the San Petronio sundial by Giovanni Domenico Cassini (AMS Historica)

“Bologna was the second city of the Papal States, after Rome, and to secure funding for such a large project Cassini had to convince the Church of its usefulness,” says Elisabetta Rossi. “He succeeded by arguing that the new sundial could provide convincing proof of the accuracy of the Gregorian calendar, which had been introduced about seventy years earlier to regulate the calculation of the date of Easter.”

Giovanni Domenico Cassini, however, had something else in mind. He was thinking of Copernicus and Kepler. He was thinking of the great questions that, barely twenty years after Galileo’s trial, could still not be asked openly, but that every astronomer of the time knew very well.

On 21 June 1655, the summer solstice, the foundation stone of the sundial was laid, and on 22 September 1655, at the autumn equinox, Cassini invited “the Professors of Mathematics and Philosophy and other curious minds” to see the astronomical instrument in action. It was a success: in the vast camera obscura of San Petronio, the sunbeam crossed the basilica’s naves, passing “between those columns, thought to be an obstacle to its description.” Thanks to this extraordinary sundial, which Cassini called the “heliometer,” it was possible to observe the movements of the Sun with unprecedented accuracy.

The solar disc reflected on the San Petronio sundial. With this instrument, Cassini achieved the first experimental confirmation of Kepler’s second law

“The question Cassini had in mind concerned the speed of the Sun’s apparent motion, which seems slower in summer and faster in winter,” explains Elisabetta Rossi. “In ancient times, it was believed that this difference was due to the varying distance between the Earth and the Sun over the year. Cassini instead wondered whether the change in speed was real and could be explained by a non-uniform motion.”

As he had hoped, it was the San Petronio sundial that enabled him to find an answer. Day after day, month after month, he managed to measure, with only minimal error, not only the variations in the speed at which the light moved along the sundial, but also the variations in the size of the Sun’s diameter reflected on the basilica floor.

“Thanks to these observations, Cassini showed that the variation in the Sun’s apparent motion is real: faster in winter, when the Earth is at perihelion, the closest point to the Sun, and slower in summer, when it is at aphelion, the farthest point,” says Elisabetta Rossi. “This was the first experimental confirmation of Kepler’s second law: the speed of a planet in an elliptical orbit changes depending on its distance from the celestial body around which it revolves.”

But is it the Sun that changes speed as it orbits the Earth, or the other way around? Cassini did not say: his calculations were correct in either case. And by maintaining this balance, between what could be observed and what could be spoken of, he continued his observations and his exploration of the Solar System.

Illustration from the volume La meridiana del tempio di S. Petronio tirata, e preparata per le osseruazioni astronomiche l’anno 1655, by Giovanni Domenico Cassini (AMS Historica)

“Cassini was always very cautious about the hypotheses of heliocentrism and the Copernican system. Yet all his studies and calculations, including the observations made thanks to the San Petronio sundial, provided strong evidence in support of that theory,” confirms Elisabetta Rossi. “Even though he never explicitly embraced the heliocentric model, his work was fundamental for subsequent generations of astronomers, and therefore for the development of astronomy.”

In 1669, thanks to the reputation he had gained in Bologna, Giovanni Domenico Cassini was invited to Paris by Louis XIV to work at the new astronomical observatory of the Académie Royale des Sciences. Bologna waited for years for his return, and his chair remained vacant for a long time. But Cassini chose to stay in France. He died in Paris in 1712.

“The San Petronio sundial is Cassini’s most visible legacy in Bologna: not only because it is an extraordinary astronomical instrument, but also because it symbolises a new way of doing research,” concludes Bruno Marano. “With Cassini, science enters a new phase: it is no longer an individual pursuit, but is shown to the public, becomes an open and collective system, where many can work together to find new answers and new solutions.”