Europe's earliest burial of a female infant

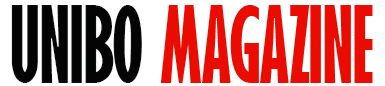

Virtual reconstruction of the burial with some of the artefacts found: bones, teeth, equipment

An international research team has discovered the earliest female human infant burial in a cave in the hinterland of Albenga, a city in the Province of Savona (Italy). The infant girl, dubbed “Neve” by researchers, lived around 10,000 years ago in the early Mesolithic when major social changes occurred as humans adapted to significant shifts following the end of the last Ice Age. The remains of the infant were adorned with over sixty perforated shell beads, four perforated pendants made from bivalve fragments and an eagle-owl talon.

The study was published in Scientific Reports (Nature). The research team behind the discovery and the analysis of the remains was coordinated by Italian researchers Stefano Benazzi (University of Bologna), Fabio Negrino (University of Genoa) and Marco Peresani (Univerisity of Ferrara) together with scholars from the University of Colorado Denver (USA), the University of Montreal (Canada), Washington University (USA), the University of Tübingen (Germany) and the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University (USA).

“Understanding how our ancestors dealt with their dead is of enormous cultural significance and allows us to study both their behavioural and ideological traits,” explains Stefano Benazzi who is a professor at the Department for the Cultural Heritage of the University of Bologna and was also among the coordinators of this study. “This discovery provides insights into an exceptional burial rite of the early Mesolithic, from which few recorded burials are known, and shows how all group members, including infant girls, were recognised as persons in their own right and treated similarly to adults.”

Researchers at work in the Arma Veirana cave

THE INFANT, THE MOTHER, THE GRAVE GOODS

A virtual dental histology of the infant’s tooth buds was performed at the BONES Lab of the University of Bologna using synchrotron imaging of a tooth obtained at the Elettra Sincrotrone Trieste centre. The histology provided valuable information on both Neve and her mother. Genome analysis and amelogenin-based sex estimation, an analysis based on a protein found in tooth buds, established the infant as female and to belong to a lineage of European women known as haplogroup U5b2b. At the time of her death, Neve was between 40 and 50 days old.

Tooth buds also made possible the analysis of carbon and nitrogen. These chemical elements showed that Neve's mother relied on a diet based on terrestrial resources – such as hunted animals – and not marine ones – such as fishing or mollusc gathering. Moreover, the analysis showed that during pregnancy Neve’s mother had undergone some physiological stress episodes, possibly related to food, which interrupted the growth of the foetus' teeth 47 and 28 days before birth.

The ornaments of the grave goods were also analysed, and they provided relevant information. Among the findings, there were more than 60 shell beads probably sewn onto a dress or leather bundle, which is indicative of the special care and attention paid to the burial. Several of these ornaments also show wear and tear, thus indicating that they were first worn for a long time by members of the group before being used to adorn the garment of the infant.

Some of the ornaments that made up the grave goods

A NEW INSIGHT ON THE EARLY MESOLITHIC

Professor Sahra Talamo of the University of Bologna conducted radiocarbon dating determining that the infant lived around 10,000 years ago during the Early Mesolithic, the first phase of the Holocene.

The Mesolithic refers to a period between around 11,000 and 7,500 years ago and represents a crucial phase for European history. It followed the end of the last Ice Age and saw the adaptation of Palaeolithic hunter-gatherer societies to a new interglacial environment characterised by the increase in forested areas and rising sea levels. This period ended when the first Neolithic groups of breeders and farmers arrived from the Near East.

"Burials from the intermediate and final phases of the Upper Palaeolithic are well documented, while burials from the Mesolithic are infrequent. For both periods, however, burials of children are particularly rare," adds Benazzi. "For this reason, the burial of Neve represents an exceptional discovery and will help us to fill many gaps, shedding light on ancient social structures and their funerary and ritual behaviour."

Virtual reconstruction of the section of the Arma Veirana cave

THE DISCOVERY OF THE BURIAL

The burial was initially found in the summer of 2017 but was fully unearthed in July of the following year. The site of the discovery is Arma Veirana, a forty-metre long cave with a bizarre hut shape located in the Erli City Council (Liguria region), north-side of the Val Neva.

The cave is located far from the coast and not easily accessible, thus planned archaeological investigation had not taken it into consideration for a long time. However, some looters had unfortunately understood its importance and they unearthed lithics and fauna associated with human presence in the Middle Palaeolithic (Neanderthal) and Late Upper Palaeolithic (Homo sapiens). A turning point occurred in 2006 when Giuseppe Vicino, former curator of the Museo Archeologico del Finale (Archaeological Museum of Finale), collected some artefacts from the soil altered by illegal excavators, handed them over to the authorities and made the site known to the scientific community.

The first excavation campaigns took place in 2015 and 2016 and investigated the artefacts near the entrance of the cave revealing layers of lithics dating over 50,000 years and typical of Neanderthals. Food remains such as broken bones ad bones of deer and wild boars with butchery cut marks, as well as charred fat remains, were also found. In the area at the top of the site, layers dating back to the end of the Upper Palaeolithic period have been found. These layers were inhabited by hunter-gatherers living between 16,000 and 15,000 years ago.

During excavation activities in the innermost part of the cave in 2017, some perforated shells were observed and supported the hypothesis of the presence of a possible burial site. This hypothesis was confirmed a few days later: after a careful and thorough excavation using dentistry tools and a small brush, researchers unearthed the remains of a small skull and the first elements of the infant girl's grave goods.

The entrance to the Arma Veirana cave

THE AUTHORS OF THE STUDY

The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports under the title "An infant burial from Arma Veirana in northwestern Italy provides insights into funerary practices and female personhood in early Mesolithic Europe". The researchers of the University of Bologna involved in the study were: Stefano Benazzi, Simona Arrighi, Luca Bondioli, Federico Lugli, Matteo Romandini and Sara Silvestrini from the Department for the Cultural Heritage, together with Sara Talamo from the Department of Chemistry "Giacomo Ciamician".

The excavation and research activities were carried out after the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage on behalf of the “Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio” for the provinces of Imperia and Savona granted the site to Professor Fabio Negrino as the scientific coordinator of the project. Research, excavations and analysis of the finds were made possible thanks to funding from The Wenner-Gren Foundation, Leakey Foundation, National Geographic Society Waitt Program, Hyde Family Foundation, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (ERC no. 724046 SUCCESS), Hidden Foods ERC and Max Planck Society.