The increase of human activity in marine environments is associated with a significant decrease in the interactions between predator and prey and between parasites and hosts in organisms living in the sea bottom of the northern Adriatic Sea. This shows a notable reduction in diversity and stability of these ecosystems.

The alarm was raised by two international studies that boast among their authors Daniele Scarponi, professor at the Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences of the University of Bologna.

The first one, published in Geology, has reconstructed how the level of parasitic infection on clams (which serve as temporary hosts) has changed over the last millennia, in conjunction with the increase in human presence along the Adriatic coasts.

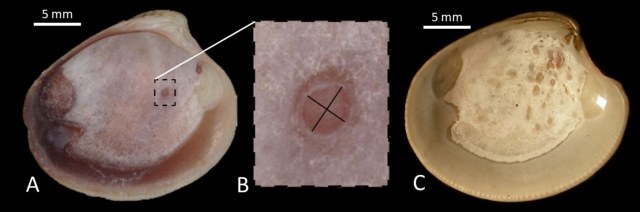

‘We focused especially on Gymnophallidae trematodes – a group of flatworms that parasitizes, among others, Adriatic clams’, explains Scarponi. ‘Traces of these interactions are small, circular depressions left on their host’s bivalve shell interior’.

To reconstruct the parasitic dynamics over time, researchers have analysed and compared samples of clam shells taken from different sources: the current sandy sea bottom located slightly south from the Po Delta, and sandy sediments deposited in comparable environments, but dating back to 2,500 years ago – a period prior to the onset of significant human influence on marine ecosystems of the Adriatic Sea.

(A) Exoskeleton of Chamelea gallina (Adriatic clam, coming from the Lido di Jesolo area, Venice); the mark attributed to the investigated parasites is highlighted by the dashed rectangle and enlarged in image B. Image (C) shows an exoskeleton of an Adriatic clam showcasing multiple parasitic traces; the clam was found among beach deposits dating back to about 2,500 years ago, discovered in the subsurface of Milano Marittima (Ravenna)

‘Our analysis shows that over the last thousands of years there has been a collapse in the abundance and diffusion of trematode traces in Adriatic clam shells’, says Scarponi. ‘We have observed that, especially in those areas characterised by a significant presence of clams, the number of shells bearing parasite traces has decreased by almost tenfold. As the parasites diversity often mirrors the diversity of the ecosystems on which their survival depends, these results are worrying’.

On that matter, the second study – published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences and, like the first one, carried out on molluscan communities of the Adriatic Sea bottoms – shows how the interactions between prey and predator have also decreased over the last decades, especially in the Po Delta area.

Researchers analysed predation traces – small ‘circular’ holes left by some gastropods on different mollusc shells – in marine deposits accumulated over the last thousands of years. In this case too, we witness a worrying decline in predator-prey interactions, especially starting from the second half of the previous century. This phenomenon is due both to the significant decrease of predator molluscs and to the change in the mollusc species that used to be more present in the Adriatic Sea bottoms.

‘These findings support other data showing, from different angles, the ongoing changes in the marine ecosystems of the northern Adriatic’, concludes Scarponi. ‘The timeline of the reduction in antagonistic relationships is associated with the increase in human activities in marine environments and the transformation of the Adriatic Sea into an essentially “urban” sea’.

The first study was published in the magazine Geology under the title ‘A sea of change: Tracing parasitic dynamics through the past millennia in the northern Adriatic, Italy’, while the second was published in the magazine Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences with the title ‘Human-driven breakdown of predator-prey interactions in the northern Adriatic Sea’.